Interview with Helen Dorey from the Sir John Soane's Museum

…Peter Thornton said this wonderful thing and he used to say it often 'we should aim to keep this house so that if John and Eliza Soane walked in through the front door, they would not be ashamed of it' and I think that's really nice. Because obviously, things can't look brand new, because they're in a historic house, but they shouldn't look shabby because it's meant to be a smart architect's house that's preserved as it was when he lived there. So that’s what we try to do.

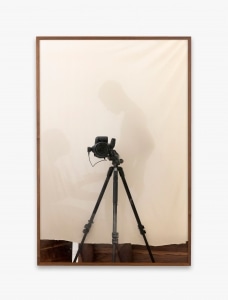

Helen Dorey, MBE, Deputy Director and Inspectress at the Sir John Soane's Museum

When looking into English architecture, Sir John Soane is a name that cannot be missed. As a British architect, he is also one of the architects who have shaped London during his career as an architect between the mid-1780s and 1837. His most well-known work is his home in Lincoln's Inn Fields - the Sir John Soane's Museum that showcases his influence from his stay in Rome, as well as his passion for Classical antiquities. The Museum is a destination for architects, architecture students and architecture enthusiasts, a learning ground for what Sir John Soane is widely known for - his inventive use of light, space and experimentation with Classical architecture forms. To me, his experimental spirit stood out; I remember vividly my first visit to the Museum as an architecture student, seeing every inch of the museum utilised as a testing ground and feeling his passion for light.

I have the pleasure of speaking with Helen Dorey, MBE, who is the Deputy Director and Inspectress at the Sir John Soane's Museum. She is regarded as one of the leading scholars of Sir John Soane, joined the Museum in 1986 and has been its Inspectress since 1995. We are extremely fortunate today to hear firsthand from Helen, who shares her insights from her work at the Museum for over 30 years. She has published extensively on the Museum, its collections and has led numerous restoration projects within the Museum. In 2017, she was awarded an MBE for her services to heritage. Let's hear from Helen Dorey from the Sir John Soane's Museum:

Von Chua:

For those who may not be familiar with Sir John Soane's Museum, can you briefly introduce the Collection and exhibitions at the Sir John Soane's Museum?

Helen Dorey:

Sir John Soane's Museum was founded by Sir John Soane. He was born in 1753 and died in 1837. He was a totally self-made man; his father was a bricklayer, maybe a modest kind of builder, so the young Soane had to make his own way in the architectural profession, and he became very successful.

He married very well - he married an heiress, and so his wealth was largely his wife's money combined with his professional income because, from a very young age, he was appointed to quite major ongoing roles in architecture. For example, he became the architect for the Bank of England from 1788, and had a good, secure, annual salary. So, a combination of good earnings and a wealthy wife enabled him to create his own house museum in Lincoln's Inn Fields. He moved into that square, near Covent Garden, right in the heart of London in the 1790s. First, he pulled down and rebuilt No. 12, and then, later on, he bought No. 13 and rebuilt that, and then, later on in his 70s, he bought No. 14 and rebuilt that house as well. As a result we have three Soane designed houses in a row on the north side of the square, and all three are today part of Sir John Soane's Museum.

… a combination of good earnings and a wealthy wife enabled him to create his own house museum in Lincoln's Inn Fields.

Helen Dorey, MBE, Deputy Director and Inspectress at the Sir John Soane's Museum

At the end of his life, however, and for many years before, he was living in just one of those three houses - No. 13 Lincoln's Inn Fields. And that is the house that he turned into his museum. The other two houses, he owned at different times, one of them he left to the nation with the Museum, and the other we bought back not that long ago. It's a complicated history. But the essence is No. 13 Lincoln's Inn Fields, which Soane pulled down and rebuilt in two phases in the early 1800s, creating his own museum, in which the building and the Collection form one single whole. The Germans use the art historical term gesamtkunstwerk, which means 'a total work of art' and this is exactly what Sir John Soane's Museum is. Soane lived in the house from 1813 until his death, and almost every year, he changed it in a fairly major way. As a result his Collection and the building were constantly evolving. It was like a draft of a poem, that was constantly amended and changed, new lines inserted, new subjects introduced. He was the sort of person who thought nothing of moving a staircase or importing 200-300 new objects at a single moment.

When he died, he left the house to the nation by a private Act of Parliament which he got passed during his own lifetime. He spent his final years preparing for his home to become a museum. And when he died in January 1837, that's exactly what happened, and it was very seamless.

Helen Dorey, MBE, Deputy Director and Inspectress at the Sir John Soane's Museum

When he died, he left the house to the nation by a private Act of Parliament which he got passed during his own lifetime. He spent his final years preparing for his home to become a museum. And when he died in January 1837, that's exactly what happened, and it was very seamless. He died on January the 20th and in March, the house opened as a museum with a Board of Trustees in place and with Soane's own Chief Assistant as the first curator. And it's been open ever since then although not all the time, Soane's original idea was that it would be opened for few days a week, and for only half the year. Today it's open five days a week for the whole year. From that point of view, things have changed a lot, but the Museum itself, because Soane's Act of Parliament required his house to be kept as it was at the time of his death, remains largely unchanged.

Von Chua:

I think it's what makes the Museum so unique compared to other house museums in the world, because it intends to maintain Soane's original intent for the Museum, in an almost untouched state.

Helen Dorey:

Yes, it has that feeling even where we have restored interiors, and we have done a lot of that over the last 30 years. We had all the evidence in the form of Soane's extraordinary archive, plans and watercolour views of the house from his day, hundreds of photographs, hundreds of archive bills, and inventories which tell you, if you work it out, where all the objects were and how they are placed in each room.

Von Chua:

So perhaps he had it in his mind, to archive everything properly.

Helen Dorey:

I think so. The strange thing is that because he was always changing things, you could say that when he died, that was just a moment. But that is the moment he chooses that it should be kept at. Undoubtedly, if he lived even longer, he died when he was 84, he would have changed it again.

The strange thing is that because he was always changing things, you could say that when he died, that was just a moment. But that is the moment he chooses that it should be kept at. Undoubtedly, if he lived even longer, he died when he was 84, he would have changed it again.

Helen Dorey, MBE, Deputy Director and Inspectress at the Sir John Soane's Museum

Von Chua:

Sir John Soane wished to preserve his house and collection at the time of his death; he successfully negotiated a private Act of Parliament in 1833 to keep the house and collection open for inspiration and education. This has been maintained since his death in January 1837, can you share how this affects the curatorial team's work?

Helen Dorey:

Of course. It is really interesting because the preoccupation of most museums is with how should they display their collection. And they're constantly redoing their galleries to try to keep up with contemporary trends, new interpretations and new areas of collecting. But of course, we don’t do that because we have Sir John Soane's house as he left it. So for the last 30 years, we have concentrated very much on restoration work and on cataloguing. By the time it got to the 1980s, the house itself was in quite a bad state. Although Sir John Soane left money to fund the running of the Museum, by the end of the second world war that had really pretty much all gone but there was the need to repair the Museum, bring back all the works of art that had been evacuated and get it open again. The Museum was very lucky to be given a government grant in 1947 and that continues today.

Although Sir John Soane left money to fund the running of the Museum, by the end of the second world war, that had really all gone. The need to repair the Museum and bring back all the works of art that have been evacuated and get it open again at the end of the war, well, there was almost not enough money to do that.

Helen Dorey, MBE, Deputy Director and Inspectress at the Sir John Soane's Museum

What this meant is that there was never a huge amount spent on the fabric of the building, so by the 1980s, a survey revealed that we had to spend £2 million on the building fabric. At that time, that seemed a huge amount. We were very fortunate that the government gave us half and then we were able to raise the other half and get going. The restoration of the fabric of the building has gone alongside the cataloguing and rearranging of the objects, which has been the subject, particularly of my research, working out exactly where each piece really was at the time of Soane's death. Because it's amazing how many had been moved, despite Soane's wish that the Museum be kept as it was. A radiator was put in so something was moved, that sort of thing. So our preoccupation has very much been about restoring the building, but alongside that, the cataloguing programme has been incredibly important as well as the care of all the objects that visitors see when they come to the house.

The restoration of the fabric of the building has gone alongside the cataloguing and rearranging the objects, which has been the subject, particularly of my research, working out exactly where each piece really was at the time of Soane's death.

Helen Dorey, MBE, Deputy Director and Inspectress at the Sir John Soane's Museum

We have 30,000 drawings and 7,000 books which are in the research library all collected by Soane. Over the last 30 years, we have been cataloguing them alongside the works of art on display in the Museum. Although you might think that this job must have been done over the last 200 years, actually, what had been done was that every different director had made his own lists. We had all these endless lists and card indexes but no central inventory where you could find out absolutely everything that had ever been written about each object. We have spent the last 30 years putting this together, that's now done, and all of our collection is available online (www.soane.org/collections). There is a lot of research still to do but that's been a huge preoccupation.

Since the mid-1990s, we have had a temporary exhibition gallery in Sir John Soane's first house, No. 12. It does get a bit complicated, but the Act of Parliament applies to No. 13, the house Soane was living in when he died, with its wonderful interiors and his collection. The other two houses we own, No. 12 and No. 14 are not subject to the Act's requirements. They're beautiful Grade I listed Soane houses but they are spaces that we can use for whatever we wish. As a result, in No. 12 since 1995, we've had an exhibition gallery and that enables us to show some of the drawings from Soane's collection of 30,000, largely hidden from public view, but also to do new exhibitions. The programme has brought a whole new sense of excitement and reaching out to the world. That has been a wonderful thing to be involved in curatorially bringing variety and stimulation and opportunities for working with partners outside the Museum.

Of course, we also have a busy education department now and they also work with all kinds of partners, most recently with patients with dementia and their carers. Their programmes also bring around 3,000 school children into contact with Soane every year and in normal time they also offer family drop-ins and workshops on site.

日本語

日本語 English

English