Murasaki Shikibu's masterpiece, the Genji monogatari

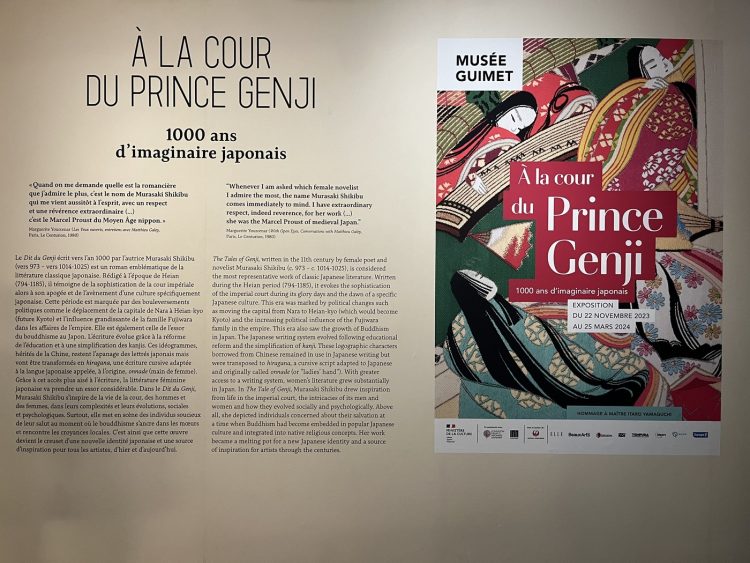

In honor of the friendship between France and Japan, the Musée national des arts asiatiques-Guimet in Paris has presented À la cour du Prince Genji, an exhibition curated by Amélie Samuel and dedicated to Murasaki Shikibu's masterpiece, the Genji monogatari. The choice of the location is far from coincidental: the museum was founded in the 19th century by Émile Guimet - a connoisseur native of Lyon with a profound love for Japanese art - and holds a profound connection with the literary monument of Murasaki Shikibu. Alongside its splendid collection of haniwa, Buddhist statues, Suji-bachi helmets, decorated fans and Noh and Gyōdō masks, in fact, musée Guimet also displays a series of picture scrolls woven by Itarô Yamaguchi and expressly dedicated to Genji monogatari, as it will be thoroughly discussed later in this article.

The presence of Yamaguchi's work in Paris equally bears witness to the deep connection between France and Japan, dating back as early as the 19th century. In this period Lyon was beaten by a fierce economic crisis caused by Nosema bombycis, a parasite that can contaminate nutritive mulberry leaves and that showed itself capable of decimating not only silkworms, but the textile industry of a whole city. Lyon, fortunately, regained its prosperity, and only when Japan stepped in as a crucial ally, becoming a major exporter of silkworm eggs to France. Meanwhile, in Kyoto, Nishijin weaving district experienced a similar economic downfall that halted only when, in 1873, a Japanese delegation traveled right to Lyon, where they acquired several French Jacquard machines. This type of loom, with its perforated card system, reinvigorated Kyoto's textile industry, managing to preserve a millennial tradition.

These are just some of the thematic nodes on which the exhibition unfolds. Visitors to the Musée Guimet can then immerse themselves in the sophisticated atmosphere of the Heian imperial court by entering the first room of the exhibit, dedicated to the major shifts happening in Japan in that period: the advent of Buddhism, the development of simplified kanji characters, and the relocation of the capital from Nara to Heian. Right in this last city, a culture of refinement and splendor blossomed, cleverly captured by many women belonging to its aristocratic milieu. Despite being sidelined from the turbulent political life of the courts, these noblewomen were close enough to capture its essence through poetry and prose, composing sagacious and delicate waka or monogatari. A series of ukiyo-e artworks by Torii Kiyonaga depicting Sei Shōnagon, Ono no Komachi, and of course Murasaki Shikibu pays homage to this splendid feminine literature, as well as several writing desks, such as the one adorned with scenes depicting Uji dating back to the Meiji era, or the lacquered wood case from the Edo period, once cherished within the collections of Marie Antoinette. The last queen of France nurtured a profound admiration for the craftsmanship of Japanese artisans in transforming lacquer into exquisite works of art. Though she possessed no understanding of Japanese, it would be fascinating to imagine her in the opulent vestibules of the Palace of Versailles, pondering the verses of Ono no Komachi's poetry displayed upon the writing case presented in this exhibition, and finally reflecting upon the fleeting essence of seasons and of her own life—or, perhaps, even of an entire chapter in the history of France.

The colors of the flowers / have well and truly passed / in pure loss / my life flows in this world / in the time of a long rainshower...

The major theme of the exhibition, the Genji monogatari, is finally unveiled to the visitor in the next room, adorned with a superb folding screen depicting the storm ravaging Genji's palace in the 28th chapter of the book. Many esteemed Western authors have greatly admired Murasaki Shikibu, such Jorge Louis Borges and Marguerite Yourcenar, the latter notably expressing “extraordinary respect, indeed reference” to what she considered a "Marcel Proust of the Japanese Middle Ages”. Despite such recognition, however, many in France remain largely unaware of the chivalrous adventures of the imperial prince Hikaru Genji. This exhibition aims to fill this gap, offering visitors an intimate glimpse into the sophisticated atmosphere of Heian court, the gracefulness of prince Genji himself, and the profound erudition with which Murasaki Shikibu captures his amorous epopee — transforming it into an expression of mono no aware, the deep, melancholic feeling evoked by the fleeting nature of beauty. Amidst a city as fast-paced as Paris, centuries before a similar concept would be embraced by French Impressionist painters (who, not coincidentally, were great admirers of Japanese art and culture), Murasaki Shikibu teaches the visitors of the exhibition that true beauty transcends the confines of permanence and must be cherished in the transient yet exquisite moments of life, similarly to cherry trees, and their fragile and ephemeral blossoming.

A wistful feeling of mono no aware permeates also the figurations of the Genji monogatari exposed in the second room. Here visitors can encounter a palanquin from the end of the 18th century internally decorated with scenes of the book on a gold background, but also yamato-e artworks, and several prints by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Kitagawa Utamaro, Hosoda Eishi, Utagawa Hiroshige, and, most notably, Masanobu Okumura. As visitors contemplate these works, the chaos of Place d'Iéna – where musée Guimet stands – fades into the background, while being replaced by a serene dimension populated by plum blossoms and bamboo rivers vanishing into the evening mist.

The following room of the museum pays tribute to manga artists like Waki Yamato, Inko Ai Akita, and Sanazaki Harumo, who transposed the Genji monogatari into the communicative codes of the 21st century, ensuring its diffusion in contemporary society. Between Hiroshige's ukiyo-e artworks and Yamato's Asakiyumemishi, the distance between centuries blurs, highlighting how Murasaki Shikibu's teachings are meaningful for all types of readers, whether they live in the Heian court or in modern-day Tokyo.

The exhibition’s concluding section addresses the history of the mechanical Jacquard loom, already mentioned at the beginning of the article, and, finally, the creations of Itarô Yamaguchi, a master weaver from the Nishijin district of Kyoto. On the eve of his seventieth birthday, Yamaguchi dedicated himself to weaving a textile reproduction of the Heian-period Illustrated Handscroll of the Genji monogatari, preserved in the Gotoh Museum in Tokyo. Reflecting on Yamaguchi's remarkable dedication, Shigeatsu Tominaga, president of the French-Japanese Sasakawa Foundation, remarked how "it's challenging to grasp the boundless energy and fervor that fueled this man for 37 years until his passing at 105, to accomplish such a colossal undertaking”. The four sets of scrolls, made of silk threads dyed with amazing precision in an infinite number of gradients for a total length of over thirty meters, are now part of the collection of musée Guimet, as a token of gratitude for the impact Jacquard machines held in Japanese textile culture. A vivid kaleidoscope of colors sparkles in front of the viewer's eyes, accompanying him in the discovery of Prince Genji's adventures, from his upbringing at the imperial court to his seductive liaisons and, finally, his fleeting retirement from the world.

Seduced by the aromas of nerikos, with suave emanations of lotus, plum and kurobo gracefully reproduced in the last room in recognition of the role of fragrances in Genji monogatari and Japanese society, visitors draw their journey through Heian Japan to a close. In this exact moment, they sense that they have grazed the very essence of a civilization's magnificence.

Concluding the article is an interview granted by Aurelie Samuel, curator of the exhibition, to ADF:

The Genji monogatari, written almost one thousand years ago, still maintains its enduring charm, delighting readers from Japan to the West. What do you believe contributes to its timeless fascination?

Regarded as the earliest psychological novel in history, this work explores themes as pertinent today as they were centuries ago: human relationships, especially those between women and men; power dynamics, intrigues, and the complexities of jealousy. Remarkably, its narrative could easily belong to contemporary literature, were it not for its courtly setting. Furthermore, although Japanese people continue to read this literary masterpiece and to study it at school, they often encounter it through the medium of manga. This is also one of the strengths of Genji monogatari: to have been reinterpreted by contemporary artists.

What insights do you believe the Genji monogatari imparts to modern-day French readers?

Genji monogatari urges us to engage in existential reflection on the passage of time; the ephemeral nature of the world in which we live prompts us to realize that we must live in the present and make the most of every instant by trying to slow down our frenetic rhythms, in order to refocus on what's essential. Today, we live in societies where long-term time does not exist, where contemplation no longer has its place, and consequently where thoughtful reflection has become secondary. Genji monogatari is a work that can be read in several ways and has several meanings.

The Genji monogatari was written by a woman, Murasaki Shikibu, in the 11th century. What, in your opinion, is the value of this feminine Japanese contribution, in a context where women have often struggled to assert themselves in the Western literary tradition?

Indeed, it is important not to forget that Genji monogatari was written by a woman. Murasaki Shikibu offers a critique of the society in which she lives from her own perspective, shedding light on the position of women during the Heian period in Japan. Her points of view, as well as her talent in depicting the constraints of living as a woman, remind us of how essential it is today for women to continue asserting their place and fighting to obtain what men most often acquire much more easily.

What is your favorite episode from the Genji monogatari, and why?

More than just a single chapter, what truly appeals to me are the vivid descriptions of nature, inviting readers to contemplation. To connect with the exhibition presented at the musée Guimet, I would mention the episode of the Storm in Book XXVIII, illustrated by a magnificent screen that showcases the refinement of pictorial representations throughout the history of this masterful and eternal literary work. "The empress had her garden planted with autumn flowers, so much so that this year, more than ever, multiple splendors were on display; and these plants of all kinds, trained on trellises and raw or peeled wood, had a striking effect, adding the beauty of their forms to the brilliance of the flowers, and the drops of dew in the sun, morning and evening, shimmered like pearls, a rare sight that, across the expanse of these fields, made one forget the hills of spring, so enchanting was their captivating freshness".

English

English 日本語

日本語